Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a large class of human-made chemicals used since the 1950s in products designed to resist heat, oil, stains, and water. You’ll find them in everything from nonstick cookware and waterproof clothing to food packaging and firefighting foams.

But the same properties that make PFAS so useful also make them dangerous. PFAS do not break down in the environment—they persist for generations, building up in our rivers, soils, fish, and even our bodies. Because of this, they’re often called “forever chemicals.”

Why PFAS Are a Threat

PFAS are highly mobile in water. Once released, they move through the environment, spreading through stormwater runoff, wastewater discharges, and more. These pathways make rivers like the Spokane especially vulnerable.

In the Spokane River watershed, PFAS contamination threatens:

Water quality, as PFAS pass through wastewater treatment systems unfiltered, or collect in biosolids as part of the treatment process.

Fish and wildlife, as the chemicals accumulate in aquatic organisms and magnify up the food chain.

Human health, especially for communities who rely on local fish for food or cultural practices.

Scientific research links PFAS exposure to a wide range of serious health effects, including increased risk of cancer, liver and kidney damage, immune system suppression, hormone disruption, and developmental and reproductive harm. Because PFAS build up in fish and wildlife, eating contaminated fish can be a major exposure route. In fact, studies have shown that a single serving of contaminated freshwater fish can equal a month’s worth of PFAS exposure through drinking water (Barbo et al., 2023).

PFAS in the Spokane River

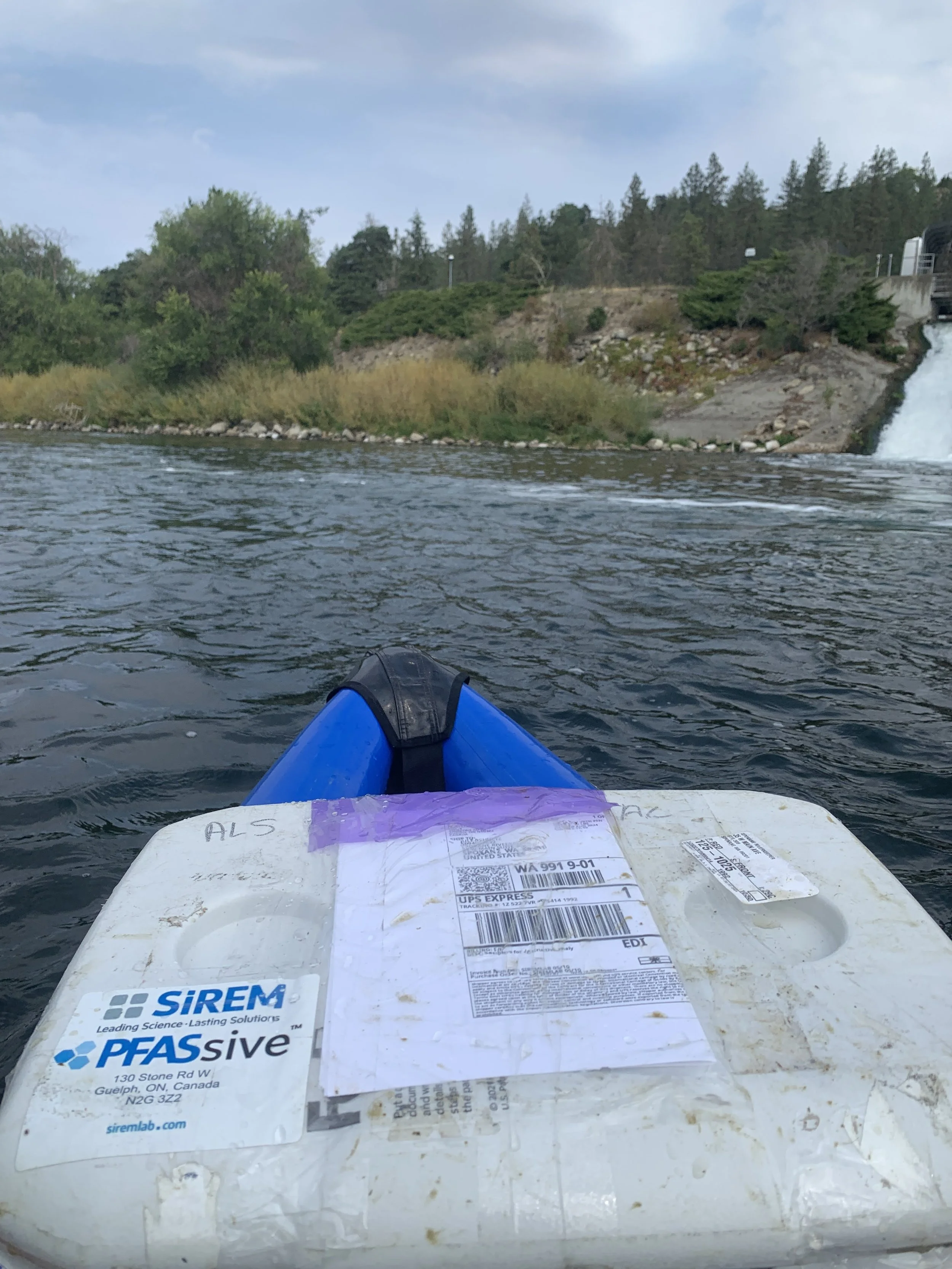

PFAS contamination in our watershed is not theoretical—it’s measurable. Spokane Riverkeeper has participated in multiple studies with Waterkeeper Alliance that have identified PFAS pollution directly in the Spokane River and its tributaries.

Phase 1 (2022): In 2022, Spokane Riverkeeper collected water samples upstream and downstream of the Riverside Park Water Reclamation Facility. Two PFAS compounds—PFHxA (perfluorohexanoic acid) and PFOA (perfluorooctanoic acid)—were found only in the samples collected below the wastewater discharge, at 1.6 and 1.7 parts per trillion (ppt), respectively. Both compounds were undetectable upstream, indicating that the WWTP discharge was the likely source. Note: this study had a detection limit of 1 ppt, meaning samples below that limit were non-detectable.

Phase 2 (2024): Two years later, a follow-up national study led by Waterkeeper Alliance again found PFAS in the Spokane River and its tributaries—this time with even higher concentrations downstream of wastewater and biosolids sites. At Dragoon Creek, PFAS levels increased more than 3,000% downstream of a biosolids land application area, confirming that these waste management practices are introducing PFAS into the watershed.

How PFAS Enter Our Watershed

PFAS contamination can enter the Spokane River through several key pathways:

Wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs): PFAS pass through treatment processes and are discharged directly into surface waters.

Biosolids land application: PFAS-laden sludge is spread on fields as fertilizer, where rain and runoff carry the chemicals into nearby creeks.

Industrial discharges: Manufacturing, product use, and disposal can release PFAS into stormwater and groundwater.

Stormwater runoff: PFAS from treated materials (like paints, sealants, or textiles) can wash off urban surfaces during rain events.

West Plains Contamination

PFAS contamination in the West Plains, near Fairchild Air Force Base and Spokane International Airport, is another potentail source of PFAS entering the Spokane River. Decades of firefighting foam use in this area have contaminated groundwater, which moves through the region’s interconnected basalt and floodplain aquifers.

Recent research by Eastern Washington University scientists, supported by the Washington Department of Ecology, is mapping how PFAS moves through these underground systems. Early findings suggest that groundwater in the West Plains may be carrying PFAS toward surface waters, including Deep Creek, Hangman Creek, and eventually the Spokane River.

This means PFAS pollution in the river may be linked not only to wastewater and stormwater discharges, but also to regional groundwater pathways—making it a watershed-scale problem that requires coordinated action.

Ecological and Health Impacts

PFAS are water-soluble and bioaccumulate—meaning they build up in the tissues of fish and wildlife faster than they can be eliminated. Larger or older fish typically carry higher PFAS concentrations, which can then be passed up the food chain to birds, mammals, and people.

These chemicals don’t just threaten fish populations; they pose a long-term risk to the health of the entire aquatic ecosystem and the communities that depend on it. This includes tribal members, low-income residents, and immigrant families who may rely on local fish as an affordable or traditional food source.

What Needs to Change

PFAS pollution is preventable—but only if we act. We’re calling on state and local decision-makers to:

Require PFAS monitoring in wastewater discharge permits.

Test biosolids for PFAS before land application.

Adopt stricter state water quality standards aligned with EPA’s human health criteria.

Ensure transparent, publicly accessible data on PFAS sources and concentrations.

Hold polluters accountable for contamination and cleanup.

Without these actions, PFAS will continue to quietly accumulate in our watershed, threatening fish, wildlife, and people for generations to come.

Learn More

To explore the national scope of this issue and read the full Waterkeeper Alliance reports, visit Waterkeeper.org/PFAS.

To learn more about the contamination on the West Plains, visit westplainswater.org.