The Spokane River is a vital resource that has attracted humans to the region for thousands of years. The river has provided food and fresh water for generations, but the arrival of white settlers in the late 1800s presented a substantial challenge to the river’s health. As Spokane’s population swelled, the amount of waste produced by the city grew exponentially. Sewer, stormwater, and even garbage dumped directly into the river without any form of filtration.

Dumping untreated sewage into the river compromised the city's drinking water source. In the early 1900s a series of typhoid outbreaks ravaged the city. In September 1909, there were sixty-four cases reported in just one week, and seventy-four cases were reported in August 1910. The outbreaks were attributed to the pollution of the river and the city was forced to find a new source of fresh water, eventually discovering one in the aquifer. Some efforts were made to alleviate the pollution but the city did not begin construction on a wastewater treatment plant until 1952, thirteen years after Coeur d’Alene opened their plant.

Voters in the City of Spokane approved a bond in the early 1950s that provided the funding to build the Riverside Wastewater Treatment Plant which began filtering the city's sewage in 1958. In 1970 the Washington Department of Ecology, a new state agency, determined that the water quality in the Spokane River was below standards. They forced the city to upgrade the wastewater treatment plant or face large fines.

Riverside Wastewater Treatment Plant: Photo of the original wastewater treatment plant that began filtering wastewater in 1958. | Source: Photo Courtesy of the Washington State Archives - Digital Archives.

In May of 1975 the city began construction on major updates to the plant. In order to complete the upgrade the city requested permission to dump raw sewage into the river for five days. Permission was reluctantly granted by the Department of Ecology and just days later riverfront property owners responded by suing the city. The plaintiffs in the case were represented by Carl Maxey, Spokane’s notable civil rights attorney. Maxey and the plaintiffs were successful in their case, arguing that the city and the Department of Ecology did not have the authority to authorize the release. The plaintiffs won $245,000 in damages and they reinforced to the city that protecting the river was a serious matter.

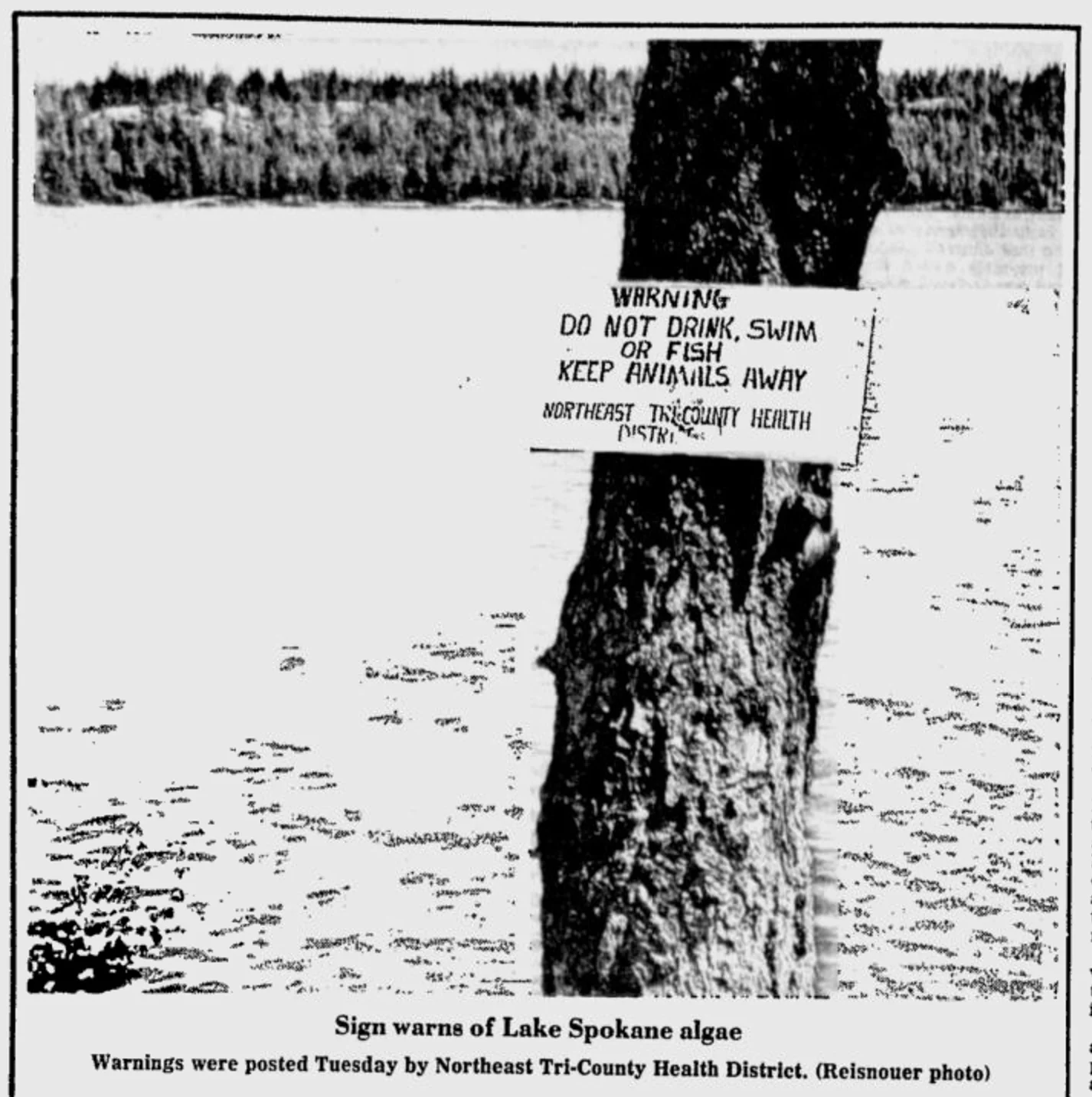

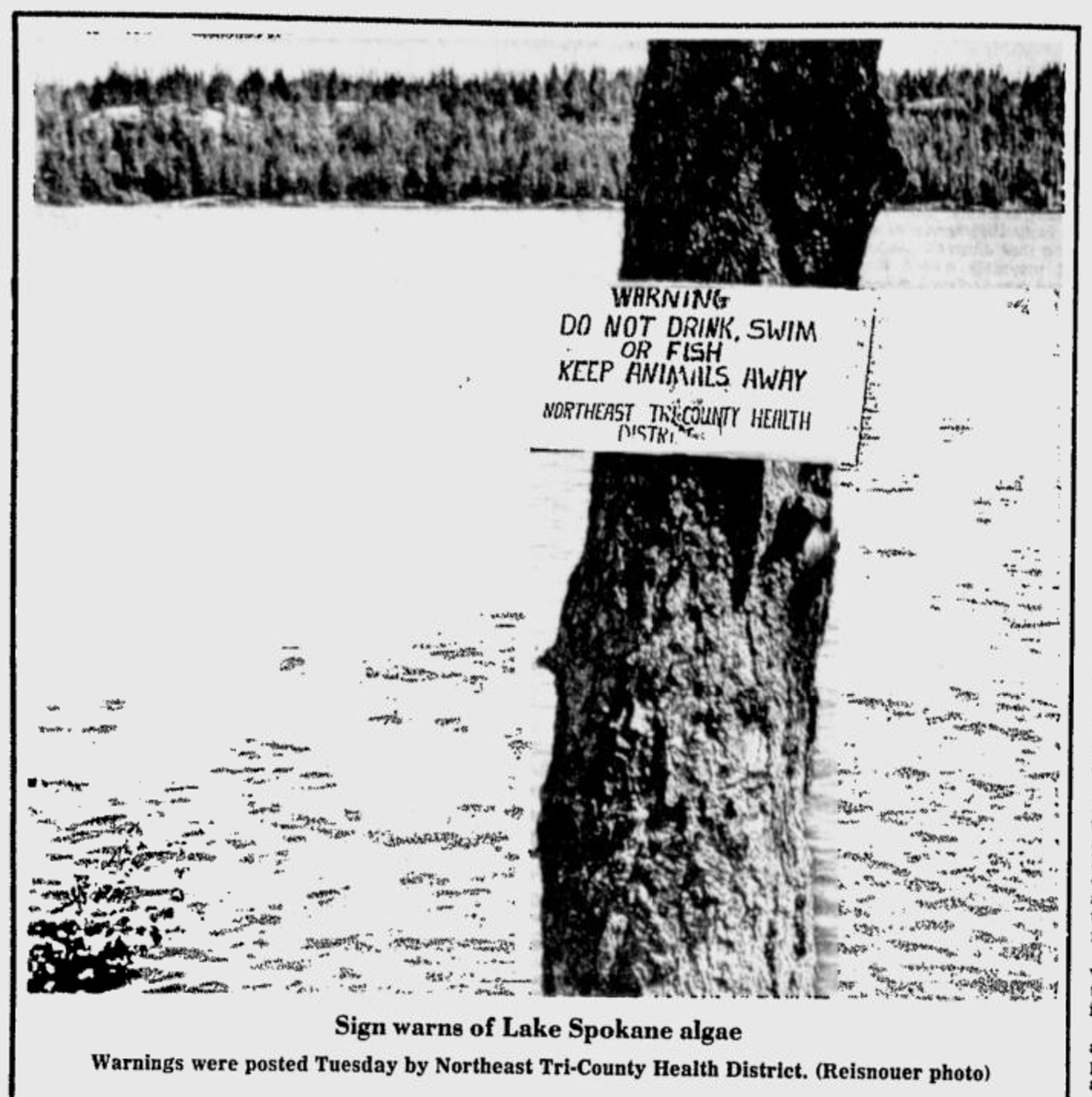

Warning: Do Not Drink, Swim, or Fish: Photo of sign posted at Lake Spokane, part of the of the Spokane River below the treatment plant, warning of toxic algae blooms caused from large amounts of phosphorous in the water. | Source: Spokesman-Review July 19, 1977.

The city completed the upgrades in 1977 and began treating wastewater with secondary treatment. This additional step removed a much higher amount of phosphorous, a pollutant caused by raw sewage. Improvements to the facility are ongoing, with another wave beginning in the 2000s.

As of 2017, Spokane was in the midst of a 126 million dollar upgrade adding tertiary filtration to the plant. With this additional filtration 99 percent of phosphorous will be removed from the water. Meanwhile the city is working to install Combined Sewer Overflow tanks across town that will prevent untreated sewage and stormwater from flowing into the river during heavy rainfall events that exceed the capacity of the plant. Although Spokane has made huge progress in protecting the river from raw sewage, the work continues indefinitely into the future.